A class-action lawsuit was filed in Los Angeles on Friday (21st) against Universal Music Group in the wake of the 2008 fire that potentially destroyed more than 500,00 recordings. The lawsuit, which was obtained by Variety, was brought on by attorneys representing the estates of Tom Petty and Tupac Shakur, Hole, Soundgarden and Steve Earle.

The lawsuit argues that Universal Music Group did not do enough to protect these artists’ intellectual property and did not adequately inform or compensate them when it happened. According to the suit, which quotes statements made on the company’s website, UMG:

“Did not take ‘all reasonable steps to make sure they are not damaged, abused, destroyed, wasted, lost or stolen,’ and it did not ‘speak[] up immediately [when it saw] abuse or misuse’ of assets. Instead, UMG stored the Master Recordings embodying Plaintiffs’ musical works in an inadequate, substandard storage warehouse located on the backlot of Universal Studios that was a known firetrap.” The suit continues, “UMG did not speak up immediately or even ever inform its recording artists that the Master Recordings embodying their musical works were destroyed. In fact, UMG concealed the loss with false public statements such as that ‘we only lost a small number of tapes and other material by obscure artists from the 1940s and 50s.’ To this day, UMG has failed to inform Plaintiffs that their Master Recordings were destroyed in the Fire.”

According to the lawsuit, the plaintiffs seek “50% of any settlement proceeds and insurance payments received by UMG for the loss of the Master Recordings” as well as “50% of any remaining loss of value not compensated by such settlement proceeds and insurance payments.”

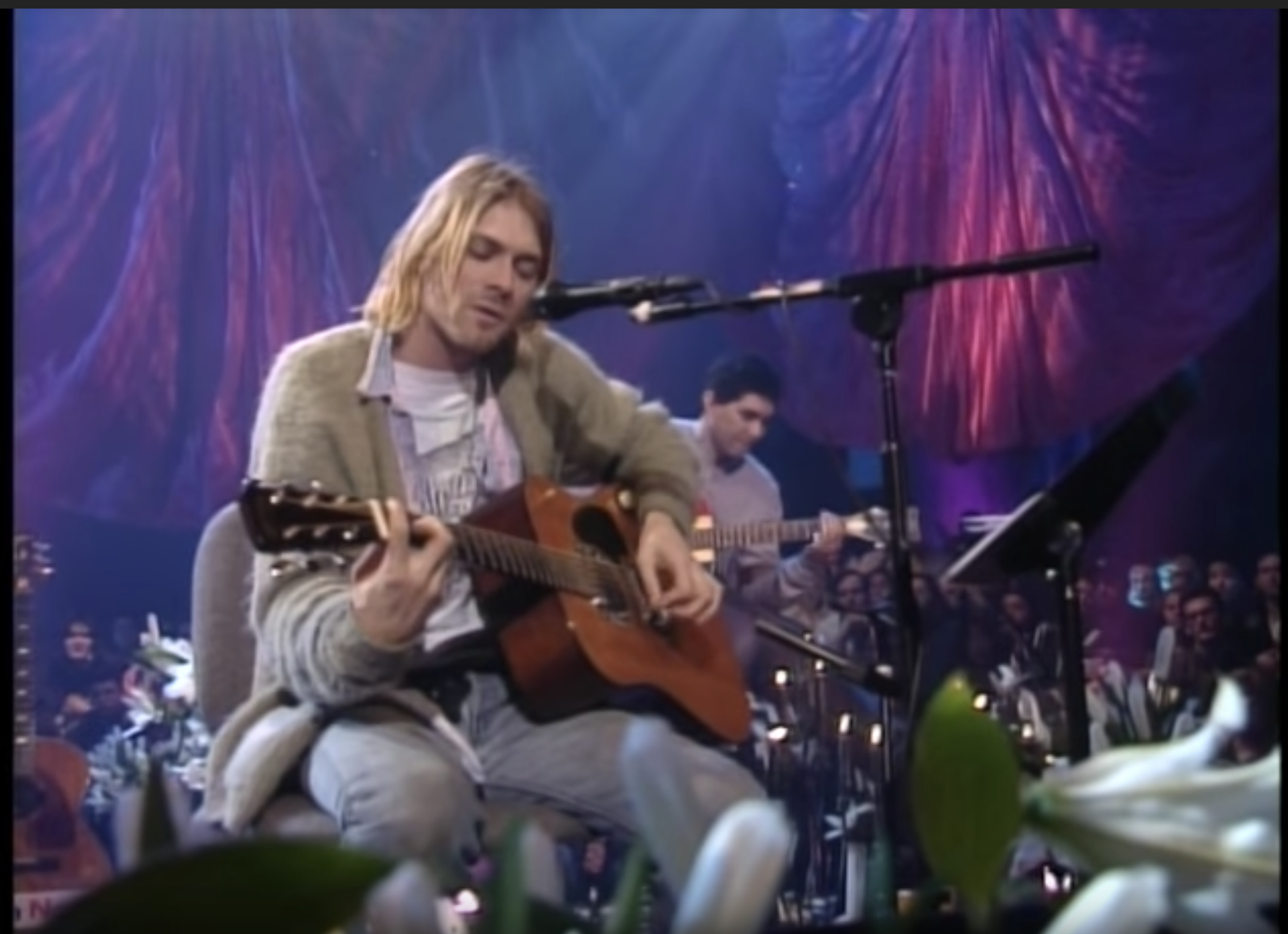

At the time of the fire in 2008, the exact amount of master recordings was downplayed, with the company at time denying that any music was lost at all. Because of this, the exact amount of recordings involved is still not completely known. However, a recent article in New York Times Magazine that cited a 2009 lawsuit filed by Universal Music Group against parent companies Vivendi and NBCUniversal, claimed that as many as 500,000 recordings had been destroyed. It is believed that master recordings going back to at least the 1940s were lost, including works from such diverse artists as Louis Armstrong, Aretha Franklin, Elton John, Tom Petty, Patsy Cline Iggy Pop, Aerosmith, R.E.M., Guns N’ Roses, Sonic Youth, Nine Inch Nails, Nirvana, Soundgarden, Hole, and many more. The 2009 lawsuit was settled in 2013 for an undisclosed amount of money, part of which the current class-action suit is looking to be compensated with.

Universal Music Group seemed to change its tune about how they want to handle the fallout from the NYT story. Though the company has claimed that the story was filled with inaccuracies, CEO Lucian Grainge is calling for transparency on the matter. In a memo to his employees, he said:

“Let me be clear: we owe our artists transparency. We owe them answers. I will ensure that the senior management of this company, starting with me, owns this.”

The same can’t be said for Vivendi. CEO Arnaud de Puyfontaine dismissed the controversy, telling Variety that:

“It happened 11 years ago and [last week’s] headlines are just noise.”

Rumors of possible lawsuits started circulating last week when attorney Howard King expressed to the LA Times that some of his clients were concerned over the possible loss of their intellectual property. King, however, seemed to dismiss the thought of a class-action, saying that his clients’ claims were:

“significant enough to justify individual lawsuits.”

According to Variety, the lawsuit could face a few hurdles based on who actually owns the tapes. An attorney not associated with the label told the magazine that when it comes to the physical tapes, those are usually the property of the label and not the artist:

“The issue is: Who owns the thing that was lost? I can’t say there is no recording agreement in history that says the physical master tape is owned by an artist, but in the vast majority of recording agreements, it’s owned by the record company. So even if the copyright in the sound recording reverted to the artist, the physical master tape is different — in almost all instances, it’s owned by the record company, and even if the recording agreement didn’t specify who owns it, because it was paid for the record company there’s a very strong argument that the record company owns it.”

King rebuked this statement, saying:

“It would just like a major-label attorney to have the dismissive attitude that the artists have no rights in the master recordings they created. As will be detailed in our complaint, the artists have a substantial interest in the recordings they entrusted to their labels and have rights to redress for the damage done, the hiding of the damage by the record company and the failure of the record company to remit proceeds from the substantial payments they received on account of the fire damage.”