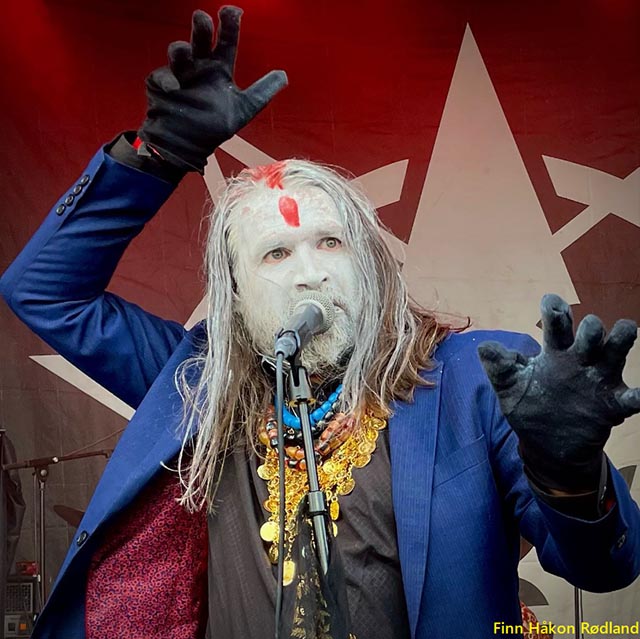

“There is a place called reality, Hidden to all men, You can reach it through insanity, But never to return again…” The sublime creations of Mr. Yusaf “Vicotnik” Parvez are both insanely real and truly insane in the most mind-blowing and rewarding senses. Verily, Yusaf embodies the ultimate black metal magician, performer, lyricist, and composer offering untold and invaluable riches.

Yusaf presents listeners with the gold they could embark upon infinite substance-fueled trips hoping to find but with only empty hands and additions to their criminal records to show. Indeed, Dødheimsgard permits the opportunity to “enter the void of what you seek.” Through his often psychedelic musical exploits, Yusaf, the dauntless “Architect of Darkness,” constructs the most mesmerizing universes in which we can dwell infinitely and expand, or rather destroy and rebuild, our self-knowledge.

Even before Dødheimsgard, Vicotnik crafted brilliant art with Askim’s Manes, one of his first bands, not to be confused with the legendary Trondheim-based outfit by the same name. The raw authenticity and dark magic emanating from Manes’ recordings should make anyone with functioning ears shiver with unfailing consistency each and every time.

With Carl-Michael “Aggressor” / “Czral” Eide, Yusaf then co-founded the devastatingly excellent Ved Buens Ende, whose demo, Those Who Caress the Pale, is now 30. Similarly, Ved Buens Ende’s full-length debut, Written in Waters, which boasts a stunning cover by Nemi artist Lise Myhre, will hit the three-decade mark next year. These titles were unleashed by Ancient Lore Creations and Misanthropy Records respectively, the sub-label and label of Ms. Tiziana Stupia, current practitioner of fire ceremonies and more. Together, Those Caress the Pale and Written in Waters represent a couple of the most mesmerizing sonic miracles that could ever befall you.

Ved Buens Ende’s gorgeously poetic yet brutal content was both greatly ahead of its time and bears something of the age and wistful character of Proust, whom the band referenced. Because of Ved Buens Ende’s ingenuity, which smashes preconceptions regarding genre definitions, Vicotnik then brought Dødheimsgard into being with Bjørn “Aldrahn” Dencker in 1994 as a vessel for exploring old-school black metal again. Anyone who is vaguely familiar with Dødheimsgard knows that while they indeed initially set sail on a traditional, albeit still individualistic path, they have produced something terrifyingly and blissfully new with each release.

In the process, Dødheimsgard has further smashed limiting notions not only pertaining to black metal but art in general. While Dødheimsgard’s inventive genius is beyond bounds, it still harbors the spirit of the early movement, which this powerhouse played a crucial role in pioneering. On a related though more superficial note, Dødheimsgard has expertly demonstrated just how to incorporate instruments that aren’t typically found in black metal, whether violin or theremin, and has made fabulous use of electronics.

Whereas so many black metal creators seem content to complacently replicate past milestones, whether their own or the feats of others, thus eliciting yawns, Yusaf’s art remains thoroughly dangerous with the potential to provoke anger, tears, and love. One sign of his true worth is that audiences frequently need much time to process his achievements. Whereas confusion might initially reign in the listener’s mind, adoration often rightfully prevails.

We have already revealed one part of our conversation with Yusaf in celebration of the 30th anniversary of Dødheimsgard. In this second installment, we’ll be discussing the beginnings of Yusaf’s journey up until Dødheimsgard’s latest victory, the explosive and unsurpassed Black Medium Current. It’s always extremely challenging when it comes to Yusaf… He has been part of several top-notch projects and forged so many masterpieces that countless important topics must simply be passed over. However, as already stated, we still managed to cover much territory.

Please remember: Whatever nice words I may have uttered down below about Yusaf’s work are severe understatements. There would be no way to properly convey my respect for either this great visionary or his catalogue, and if there was, it would be so horrifically positive as to be unbearable. Take it from this painfully opinionated former black metal columnist, a.k.a. me: Yusaf makes all but a minuscule number of his peers appear as no more than sickly beasts on their way toward the pet shelter for their inevitable jab of euthanasia.

You’ve had a lot of great stage names over the years: Vicotnik, Mr. Fixit, Mr. Fantastic Deceptionist, Viper, 498, and Osama Bin Askeladden — I love Endwarfment. But I’ve never known why you chose Vicotnik for Dødheimsgard and what it means.

That’s my first one, and it’s from the realm of fantasy. I picked up this name from a bit more of an obscure world than Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Many people took their band names and pseudonyms and stuff like that from Tolkien. So, I guess, I continued in that fashion. But again, I went to a more obscure world. A few years ago, I got in touch with the author through a friend of mine. He said I made that name now more famous than he did when he wrote the kind of role-playing adventure with Vicotnik as the villain of that world. You can say it’s basically equivalent to Sauron in Lord of the Rings but in another realm.

On social media, there’s a beautiful picture of you, the future “Supervillain Outcast,” looking forlorn [and totally cool] among his classmates. Could you please give some context?

Yeah, you’re thinking about the class picture. That’s a very-very honest depiction of me at that time, how I felt, and how I was perceived by everything around me. So, it’s a very accurate portrait, actually. Of course, I was really young. So many things have happened since then. But I remember that school year, I was in 13-14-15 fistfights or something like that. Everybody in the school area had a bone to pick with me. I remember being in the office of the head principal, and even he couldn’t stand me. Even though people were attacking me, he sort of blamed me. He said: “You’ve been in so many fights now.” And I tried to remind him: “Yeah, I’m in fights because people are picking it with me. So, I’m not in 13-14-15 fights now because I started them.” But it didn’t matter, you know. You were the supervillain. People treated you that way. So, eventually, you just devoured that role and took pride in it. So, okay, if I’m the supervillain, I’m really going to be it as well.

Did tape-trading early on inform your taste in music? Do you have any memorable tape-trading experiences that you’d like to share?

Oh, yeah, the tape-trading years were very rewarding in the sense that you could get ahold of music, and even very obscure music, and build this community. I’ve always felt that’s what the extreme metal scene, especially black metal, grew out of — the people who traded tapes and letters and then eventually became the bands, the labels, and distributors. You know, like a whole industry, or a whole business, grew out of these, I don’t know, 200 kids around the world trading tapes. So, I guess that’s my best memory of it — the overarching narrative of what it was and what it became. In a sense, it’s still going on because it’s still the same people. I had a show last year in Gothenburg, and the bartender there reached out. He said: “Hey Yusaf! How are you?” And I was: “Do we know each other?” And he said: “Yeah, we used to trade tapes in ’92.” And now, he is part of running a metal bar with concerts and my booking, obviously. So, it comes full circle in a way.

You didn’t get your first guitar until you were 15, but you borrowed in the meantime. Could you please tell me about finding your way with guitar?

I remember I got to borrow an acoustic guitar while I was waiting for my own first guitar. An acoustic guitar wasn’t really what I wanted. I wanted an electric guitar with an amp, loads of peddles, and stuff like that. But, I guess, the acoustic guitar just had to do. And if I remember correctly, the guitar was broken. So, it didn’t even have six strings. It had four strings — D, E, A, and G. I had to kind of figure out how to write riffs just having those four strings available. That was the first half year or year or something like that playing guitar. Eventually, I got to borrow a proper six-string guitar, but I had to wait for a long time because I’m not from a place where you could get gifts that are that expensive. You had to save up for it yourself and be interested long enough that you could buy yourself a guitar.

I really love Manes, your band. And I think that it’s cool that there’s a split [Pro-Gnosis-Diabolis 1993 / Solve et Coagula] with Tor-Helge Skei’s Manes. The funny thing about that comp is that it combines everyone I respect — you, Cernunnus [Tor-Helge], and Niklas [Kvarforth, the one and only, blessed be His name]. So, is there anything that you would like to say about that release?

I remember back to the days when we decided to call our band Manes, and we were very happy about the name. We did a demo and stuff like that. And then, a couple of months down the road, we discovered that there was this band from Trondheim with the same name. We were considering whether we should give them a lot of shit and scare them out of using this name because we wanted it for ourselves. So, the first thing we had to do was to listen to their music because it would obviously be very shitty, and that would give us an edge to really threaten them out of using that name. But instead, we found out that, fuck, this demo is so good, you know. It’s so deep, the atmosphere. So, we were, like: “Nah, we just have to commit to the fact that we share the name because this is such a quality band that they deserve it as much as we do.” Yeah, I remember that very strongly.

Wow. Again, above all, my favorite creators are you, Cern, and the ever charming Niklas [and a certain man from Bergen]. Obviously, on Black Medium Current, you say “Dronningens gate” twice, and that was a really important place for you when you moved to Oslo and away from Askim, where you formed Manes. When I spoke to Nag from Tsjuder, he said that Mayhem tried to throw a motorcycle through the window of the nearby rehearsal space. Do you have any wild memories from that era you can share?

You know, I would almost say that black metal was, at that point, the new punk. We were all young punks with no money in our bank accounts and, many times, no place to live. So, we kind of lived on Elm Street and also the rehearsal place on Skippergata, which is the parallel street to Dronningens gate — it was really close by and where all the bands were rehearsing like Ulver, Mayhem, Arcturus, Dødheimsgard, Ved Buens Ende. Tons more bands were sometimes also coming over to borrow the facilities — like Gorgoroth borrowed our rooms when preparing for a show in Oslo and stuff like that. So, yeah, there was always something crazy going on and, of course, a lot of drug usage and excess of everything. When you’re young at that stage, you think your mind and your body will be able to surpass and win over anything, and that was reflected in our small community.

It’s kind of crazy how in Dødheimsgard for recording purposes, you started out on drums and backing vocals because you’re phenomenal at everything. Could you please tell me about building your skills as a vocalist over the years?

Yeah, I started as a guitarist/vocalist. And then, what the future held from ’91, when I started off doing the guitars and the vocals in my first band, until ’94, when we formed Dødheimsgard and Ved Buens Ende, was just circumstance in a way. I started bands with people who also had a desire to do vocals. In Ved Buens Ende, we split it up. I’ve also done some vocals for Dødheimsgard over the years. But I was happy to do something else. I was never really a drummer either. When we started Dødheimsgard, we had no drummer. And when we got Fenriz, he wasn’t really that keen on playing drums because he did that in every other band. So, we just moved everybody around to unfamiliar positions, I guess, and hoped that would affect the music in a positive way, that it would take us out of how we normally wrote music and add something special to it. And I think it did. I think we managed to do that.

Peaceville will reissue Kronet til Konge this December because it will be 30 next year. Is there anything that you would like to share about Grellmund, whose songwriting was incorporated into “When Heavens End”?

He was a mutual friend of mine and Aldrahn’s. We knew him separately. He was a friend of ours before me and Aldrahn became friends. What one can say is that the bond between me and Aldrahn arose because then we didn’t have Grellmund anymore, so it was a way to kind of close the gap, I guess. He was a very authentic person and a very troubled person. I’m glad we made that decision to include one of his riffs, so it’s immortalized. Grellmund also came from Ulver. He was also one of those guys that contributed a lot to the craziness going on in the rehearsal spaces around that time. To fuse your other question with this question, I remember me and Grellmund came home from a night of heavy drinking. We were on the fourth floor of the rehearsal space, and he was hanging out of the window with his back way out, just hanging by the curtain. He was like: “Yeah, Yusaf, we should just let go! You know, come on. Let’s let go!” And, luckily, I managed to talk him back into the room before the curtain broke. But what really happened to him is very unclear, actually — what really happened that night when he was found dead. But it was definitely in the cards that something would befall this person because he lived in utter chaos.

That’s tragic. Before moving on from Kronet, I’ll mention that you said that Dødheimsgard would have become more popular if you had stayed on that path. Each of your albums is mind-blowing, so it’s absurd to think that listeners wouldn’t just be ecstatic about your ability to always deliver something brilliant in a new way. So, then there was Monumental Possession, which has been described as a jump further back, a homage to ’80s black/thrash. Kai [Halvorsen] was one of the engineers for Monumental Possession. Obviously, you have a history and now work with him again in Dold Vorde Ens Navn. Was the Monumental Possession era when you met him?

No, no. I’ve known Kai for a long time, before we started doing bands and stuff like that. My grandparents come from a place in Oslo called Veitvet, and this is also where Kai grew up. So, I met him when we were, I guess, 10 years old, 8 years old, whatever. But then, it was in a completely different context. When I eventually showed up at Stovner Rockefabrikk wanting a job when I was 16, he was there. He was there already working, and I recognized him. We started talking again. So, our fates have been linked in some way. There’s been a lot of back and forth with Kai. He was in Dødheimsgard as well. I really wanted to use him again on the Supervillain album, try to get him back in the fold then… Unfortunately, he wasn’t available at that time. So, I was really happy that now we have the opportunity to do some music together again.

Garm did mastering for you for Monumental Possession and Satanic Art, and he contributed to the Aphrodisiac album. Could there ever be an Aphrodisiac reunion?

Yeah, we talk about it sometimes over a drink. But right now, I want to do two things first with Svein Egil [Hatlevik]. One thing I want to do is for him to co-write a song with me for the next Dødheimsgard album. I think it’s the right time now, 25 years later, to have him write some music with me again. And I also want to contribute something to Fleurety. We talked about that as well, me doing some bass or some vocals or whatever. We’ll figure it out. I think those are my two priorities above doing another Aphrodisiac thing. Let’s see when I manage to fulfill those two obligations, and then maybe it will be time for a new Aphrodisiac album. It’s probably the most obscure release we ever did. I think it sold a couple hundred copies. I’m surprised I get asked about it, but I’m pleased.

Well, Nonsense Chamber is a fantastic album. [It’s beyond that, but my powers of description stop where Yusaf’s sonic wonders begin…] And I hope that more people will discover it. So, yeah, I really love it. You have Kierkegaard on there, you have Jeffrey Dahmer’s lawyer, you have so much cool stuff…

One guy wrote to me once, and he also had a great relationship with Nonsense Chamber. He said he came home late at night after drinking and taking some mushrooms or whatever. He went to his room in his apartment, I don’t even remember, and he put on that record, Nonsense Chamber. He sat there for a while, and after maybe 5-10 minutes, he got terrified. The depth of darkness was so overwhelming to him in that state, so he just had to turn off the music. He couldn’t stand it. He got literally afraid sitting there in that tense atmosphere. And he said: “I’ve never listened to that album again after that.” So, he reached out and shared that with me, and I thought that was pretty powerful.

Yeah, it’s a different kind of darkness. And it’s a wonderful-wonderful darkness. In fact, it redefines darkness. So, on the topic of Satanic Art, one really great black metal musician told me he thinks that “Traces of Reality” is the best black metal song ever. You already covered Svein Egil, who I was going to ask you about since he did such incredible work on Satanic Art and 666 International. For the sake of readers, I should probably note that you started creating the material for both titles several years before they were released. [And yet, they still seem centuries ahead of even our current time.] You were already making experimental music with Ved Buens Ende, so the more, and I know there are issues with this word, “avant-garde” approach was nothing new for you. The point is that as far as 666 International is concerned, it’s insane that your fans were physically fighting you. Not wanting an artist to grow and judging an album before allowing time to properly process it are the stupidest things a person can do.

Thinking about how black metal itself was such an opposition to conformity in music and in culture, you get somewhat surprised by just how conformist it became just a few years into its own existence. But that’s what happens with things, I guess. As long as something gets more attention, people can only accept it under the parameters that are presented. Anything beyond that will kind of be beyond comprehension. I think it’s more interesting to expand instead of just kind of going by the accepted notions of what something can be because then it will stagnate. Then, it will never have the potential to be anything else. So, that’s why I try to explore the boundaries. That also can add some new inspiration to new players, and they can join me in the task of kind of growing the genre and growing the understanding of what black metal is.

As far as Supervillain Outcast goes, Kvohst joined you at Beyond the Gates this year. How was that experience?

Great! We’ve always stayed in touch since, I guess, the end of the ’90s. Even if we went our separate ways musically, it’s always been cordial, and we have a very close and warm friendship. Whenever I can have him available to share the stage with me, it’s always such a treat. He said the same thing: “Whenever I have the possibility, I’m there.” I like that role that Dødheimsgard has in the sense that it’s not a stagnant piece of something that’s committed to just four people. It’s basically kind of expanded into being a musical collective concerning many people that laid a lot of great work into this band and can pick that up again whenever and still contribute and adorn what Dødheimsgard is. So, yeah, we have some plans for Inferno Festival and also for next year’s Roadburn to do some cool renditions of both past and present material.

Speaking of Inferno, you’ve DJed around the fest at Kniven. What are your DJ picks?

I don’t think I’m DJing next year, but I have done it. I’m a lazy DJ. My big thing is communication. I communicate the music. I look at the crowd inside the room, and I try to figure out the best line of music, which is hopefully stuff I like myself, and then stay for another beer or five. And if I can draw them closer to the DJ booth as well and engage in a conversation about the arts and music and stuff like that to increase the enjoyment for both them and myself, then that’s a good DJ night for me.

A Umbra Omega, to me, is the height of art. I can’t say enough good about that album. Aldrahn’s cadence and performances are very actorly there. I believe that you said that he was involved in theater in the ’90s, but your performances are very theatrical as well. So, I was wondering if you’ve also had experience in the theater.

It’s me who did the theater, actually. To my knowledge, Aldrahn never did any theater. I have some experience doing theater with an underground theater group in Stockholm at the end of the ’90s. I always hoped there would be more, but then other things turn up, and you have to spend your time on that instead. But, hopefully, one day I can return to that stage. I really love becoming the role, even outside the stage itself. If you have a month or two of performances, you stay in character for that whole two months, not only the sixty minutes you are onstage, but for that whole extended period, you just stay in that character.

You throw away a bunch of material, which is a shame. [And I hope you salvage as much as possible by organizing a compilation, as you’ve discussed elsewhere.] But you said that in A Umbra’s first incarnation, it was kind of like “Supervillain 2,” which you discarded. Anyway, you had the idea to smash A Umbra together with Black Medium Current. Do you think you’re going to go with that?

You know, it’s taken a lot of different shapes and forms. Like you said, the first rendition of A Umbra Omega was like “Supervillain 2,” and then it kind of became its own entity. I threw a lot of material out, and I kept bits and pieces, parts I thought would matter. I think the big change there is that during the Supervillain period and the few years that followed, my mind was very set on being a metal band in the sense that I wanted songs that were very definable and easy, having the right amount of beats, basically. And also, I wanted the dynamics to really work on the stage. I was very industry-oriented and maybe thinking about having a live career and doing that 200-300 days a year or whatever. That perspective changed during the writing of A Umbra Omega. It changed from me having an industry mindset to me just not caring about that anymore and finding a more personal rooting to make music. Obviously, then I didn’t feel that the first renditions of the songs for A Umbra Omega represented that. It was too made for a specific market. I’m not saying I made music I didn’t like. Of course, I liked it, but it was more gimmicky in a way. So, I needed to get rid of that and start again where I could dwell a bit deeper in an honest rendition… And maybe also, for the first time, touch a bit upon vulnerabilities and darkness as a vulnerable state, instead of all these metaphors of dark warriors and the “haha, I’m so cool” kind of approach to it. Black Medium Current links up with A Umbra in that regard because it’s a further exploration down the personal rabbit hole of what I started on A Umbra. The music on Black Medium Current is very evocative. It’s very emotional. And those emotional states are meant to portray what the topics are and vice versa, of course. I always imagine this woman. She’s standing in the forest 1,000 years ago or whatever, it doesn’t really matter. She lost her children to disease or to war or whatever, that also doesn’t really matter. But she’s still doing labor. She’s still doing her duty in the forest. And while she’s doing it, she’s singing this melody for herself. It’s not a melody she knows. She’s just expressing sadness. I think there’s some utility to that. There’s something that’s universal and timeless about the fact that she’s expressing an emotion and a comfort through her singing. I wanted to touch on that. What are those melodies?! What is that primal, instinctual music that resides within us?! I’m exploring that side of music.

The last time we spoke, which was before Black Medium Current’s release, I told you that I cried when I was listening to it. [And I still do both because of its profundity and its excellence.] You said that someone else said the same. So, I was wondering if that was Finn Håkon Rødland [because I know he was a huge advocate of the album and one of the first people, or probably the very first, to start spreading the word of its genius].

It wasn’t Finn Håkon, but, yeah, Finn also heard the album before its release. He reached out to me extensively and wrote about the 13 passages from the album that touched him deeply. I think that was my ambition, that it should latch onto something personal. Black Medium Current is kind of the universal state of the black mind, something that exists outside us but also within us.

Read part one here.

Feature Image Photo Credit: Finn Håkon Rødland