Yusaf “Vicotnik” Parvez of Dødheimsgard is a genius who even puts other geniuses to shame. On the one hand, there is very little that we can say about this figure: The proper reaction to his art is silence. Indeed, Yusaf’s creations render us speechless with mouths agape; the praises of this luminary would be impossible to sufficiently sing. Yet, he is, of course, also a topic that can be explored infinitely. A limitless creator, Yusaf leaves those with the ears to hear with endless thoughts and images they feel compelled to express.

Mr. Parvez has established himself as one of black metal’s most important pioneers. However, with Dødheimsgard and beyond, he has expanded the genre to the point that he has obliterated all imaginable preconceptions with the effectiveness of an atom bomb. I view Yusaf as the movement’s top ARTist insofar as he wields an unsurpassed ability to paint stunning visuals within the framework of his dazzling masterpieces. His work is cerebral, poetic, and sophisticated while likewise conjuring the very most abysmal and brutal aspects of existence and its antithesis.

In my ever so arrogant and stubborn opinion, Yusaf and his finesse are responsible for some of the greatest releases ever made. I regard Yusaf as the equivalent of Proust tinged with Lewis Carroll, perhaps also laced with some Dalí, and compressed into a sonic pill to be marketed as a cognitive stimulant with the side effect of deranging and rearranging one’s senses by way of an emotional rollercoaster constructed with strategically placed loose bolts.

It has been 30 years since Yusaf birthed Dødheimsgard with Bjørn “Aldrahn” Dencker. Not long before and still roughly 30 years ago, Yusaf similarly co-founded the legendary Ved Buens Ende with Carl-Michael “Aggressor” / “Czral” Eide. It is already apparent that I adore Dødheimsgard, and please, whatever you do, do not make me start attempting to describe Ved Buens Ende. Like DHG, VBE is one of the most worthy bands of all time.

Within the realm of black metal, only the best could likewise be said of Strid, of which Yusaf has served as an integral part for roughly 15 years. The same applies to the younger Dold Vorde Ens, a supergroup of friends fronted by Yusaf and conceived in 2016 by ex-Ulver’s Håvard “Haavard” Jørgensen and ex-Dødheimsgard’s Kai “Cerberus” Halvorsen. I still stand behind my statement that Dold Vorde Ens Navn’s “Mørkere is an album so elite that it belongs on a shelf with Tchaikovsky,” and hold the EP that preceded it, Gjengangere i hjertets mørke, in the highest regard as well.

Let’s not forget criminally underrated gems like the experimental Nonsense Chamber by Yusaf’s all too potent outfit Aphrodisiac. Then, there are Yusaf’s feats of a crushingly hilarious nature with Endwarfment. Yusaf likewise lent his supremacy to England’s Code and Greece’s Naer Mataron. He has furthermore appeared as a guest with so many celebrated bands, such as the disgustingly excellent Slavia (Rest in Power Jonas Raskolnikov Christiansen), the international supergroup Doedsvangr, Fenriz’s Isengard, and the ever polarizing household name Dimmu Borgir.

We have chosen to mark the occasion of Dødheimsgard’s anniversary with a two-part conversation with Yusaf. The beautiful press statement for Dødheimsgard’s latest record, Black Medium Current, expressed the notion that confusion is a precondition for intellectual honesty and freedom. In true Dødheimsgard fashion, let confusion reign. We have decided to present the second half of our talk first in order to also celebrate the unveiling of Doedsmaghird’s Omniverse Consciousness, which we have been ever so impatiently awaiting since 2022.

By now, I have conducted a ton of interviews, and Yusaf has definitely amounted to the most complicated subject I have attempted to tackle. I could literally ask the prolific “Supervillain Outcast” a million questions about his astoundingly varied and impossibly deep body of work. You had better thank your god, whether above or below, that I was too overwhelmed by the daunting task at hand to articulate all that I had intended. Otherwise, yours truly, a misanthrope even among misanthropes, would have morphed into the most horrifyingly gushing interviewer of all time.

Honored isn’t even the right word to describe a meeting with a visionary as immortal and distinguished as Yusaf. Thus, let’s finally dive into this enlightening discussion without any further adjectives.

It’s hard to even speak about Black Medium Current because the whole album is beyond phenomenal, and there is endless subject matter to discuss. During our last conversation, you explained that you incorporated the concept of “the veil of ignorance,” which relates to empathy. You mention a veil twice on Omniverse Consciousness. You’ve said that you work things out through your music like you try to become more morally righteous and a better father and whatnot. It’s interesting because you’re obviously an originator of the genre, but some people are like: “Black metal has to be hateful! It has to be about Satan.” [Truly Satanic music is great, but bands often merely appropriate Satanism as a theme to sound tough without understanding it.] Your art is extremely varied and encompasses the full gamut of emotions, and so few bands can pull off a more complex alternative, as you do, within the genre. For example, Ved Buens Ende has romantic themes, and it takes your genius to make that work.

I guess it has to have some utility beyond being destructive. I think the similarity with someone who says, “No, it only has to be about hate and all that stuff,” is that we have a lot of those topics within our lyrical content, but the reasoning for it is different. There’s a lot of negativity in Black Medium Current, but this darkness is represented as something you go through and build upon, instead of just presenting it as something that’s horrible. That’s where the utility part comes in, that the story has to lead somewhere. It can’t just be a soulless representation of a million deaths or whatever. I think there also has to be some intellectual understanding of what that implies in that specific setting. I think that’s what sets us a bit apart. And when I say I want to be a better father or a more complete human being, it’s because, in a sense, the process is about trying to discover the things about you that are made-up or untrue and the things about you that are true. There are so many things that you carry around with you that you experience as your own state of mind, but they’ve actually just been passed down for generations or are tied to some unresolved issue or situation you found yourself in in the past. That’s what I’m digging at. I’m trying to identify those things, and then tie them up, and then take a dive in them, and then write about the experience of doing that, basically.

Obviously, Black Medium Current is a philosophical album in part. In an interview, you said that you like Georges Bataille, and he’s one of my favorite writers. Do you have any favorite books by Bataille?

Eroticism. That’s the book that made the biggest impression on me. I quoted it endlessly. I think I was 18 or 19 when I read it. It just presented me with so many perspectives about how to interpret the information around me that I had never seen before. I had never had topics presented in that way. It impressed me immensely. It impressed me to the degree that it affected how I wrote lyrics and made music myself, you know, how I challenged established ideas. Like you said in the previous question, so many people think: “No, if you do black metal, it has to be this or that.” They’re kind of ignoring the fact that that’s only their opinion, and their opinion is as valuable as any other opinion. I’m not saying that from a humane perspective. I’m saying that from a philosophical perspective, that one opinion really doesn’t have any more automatic plus points than any other opinion. It’s just the same kind of statement logically.

I was such a nag about the Doedsmaghird album and kept asking for it. It was supposed to come out six months after Black Medium Current. What caused the delay?

It was meant to be a solo project. I think I was in line to almost reach that deadline, but then Camille [Giraudeau] came along, and he really wanted to do something together. First, he proposed creating a new band or me joining one of his bands or whatever. I felt the easy and more practical way was just to say: “Hey, man, I have a spot for you in Doedsmaghird. Should I send you the tracks, and you tell me what you think?!” It all went from there. In the end, that benefited the product. He could bring his interpretations and added a lot. We had to spend more time on the album, remove the programmed drums and whatnot, and get his way of drumming in and set that up. He had to learn the songs, add the contributions, and stuff like that. So, yes, it took more time, but it was worth it.

Camille plays with Svein Egil [Hatlevik, formerly of Dødheimsgard] in Stagnant Waters. He and Dødheimsgard’s Lars-Emil [Måløy] are in Void together. And Camille performs live with Dødheimsgard. Do you think he’ll ever record with Dødheimsgard?

You know, I can’t predict the future. As it is now, he won’t record with Dødheimsgard, but we have Doedsmaghird, and we have plans to make more music. I’ve also said to Cam that he can get a certain percentage of the music to write for the next album. My plan is to divide it between the three of us — Camille, Olivier [Côté], and myself. So, that’s the plan for the next record: to give each of us like 33.3333-endlessly percent of the music material.

How did you first connect with Olivier? [For curious readers, he didn’t just contribute to Omniverse Consciousness, but he also penned the lyrics to A Umbra Omega’s “Blue Moon Duel.]

I think the first time I talked to him, he did an interview with me for a metal zine in Canada… I guess, it’s Canadian. I don’t even remember. But he kept getting in touch, and I didn’t really notice at first. I remember once I said: “Yeah, we’ve known each other since 2009.” And he told me: “No, no, no. We’ve known each other since 2005 or something.” So, I didn’t really notice him until 2009, and from there, we’ve developed a very close relationship. He’s my go-to guy when I make new music or write new lyrics. I always share portions of them with him, and we discuss them. He has a very-very potent way of engaging with the arts, and we can talk in a very interesting way. Adding our conversations back into the music helps me. It gives greater depth to what I’ve written when I’ve talked about it and know, to some extent, how it comes across, what he felt, how he breaks it down analytically, and what impressions he gets, basically.

Obviously, Ole Teigen has worked with you in the past in Dødheimsgard. He helped with the music for Omniverse Consciousness’ “Requiem Transiens” — Black Medium Current ends with “Requiem Aeternum,” which he had nothing to do with but should be noted regardless. How did Ole come into the fold with Doedsmaghird?

It was always in the cards that we would do something together again, and eventually, I kind of knew that narrationally the Doedsmaghird album had to kind of mirror Black Medium Current in some shape or form. I needed a piano spot there, and he was, at the time, doing his solo stuff with Ole Teigen, which was mainly piano-based music. So, I knew he was in that mode that I was searching for. I reached out and pretty much ordered a piece of work. We sent it back and forth, doing the vocals for it. And we have kind of agreed that we should do it more, that there was something there that can be explored further.

[And, hopefully, whatever you do next with Ole Teigen will feature his visual art on the cover.] I was wondering: Who are Frode Ophsal and Ole Svensli? Also, I kind of thought it was funny that they wrote the only Norwegian texts on Omniverse Consciousness because you went back and forth between languages beautifully on Black Medium Current.

Both of them are people I grew up with, and so I’ve known them since the first grades in school, basically. To start with Frode Ophsal, a couple of years ago, he was pretty much spiraling out of control. Of course, we had many conversations. Part of some of these conversations went into an artistic form. I saw that he was very keen on sharing his experiences of spiraling down into the abyss. So, I pretty much asked him if he could try to capture that experience for me on paper and told him that I could make music for it and present it. And so, he did, and I think he managed fantastically to catch precisely that. I see that he’s gotten help now, and that’s good. So, he’s at least on one foot now and not three-fourths in the grave anymore. With Ole Svensli, he was a very close friend of mine and also a metal guy. He used to do bands back in the late ’80s / early ’90s. He was a bit older than me. When I was a kid, he was one of the guys I looked up to in a way, not necessarily on a human level or whatnot, but especially because he was playing in bands and making music and making art and stuff like that. He fell into a really-really-really bad depression. And eventually, this depression cost his life. He chose to end it himself. Fast-forward many years, his ex-wife reached out to me, and she said: “Yusaf, I was tidying the loft (or the basement or whatever), and I found this piece of writing that Ole wrote a few months before he died.” And she shared it with me, and I was like: “Oh, this is really powerful.” I wrote her back and said: “You know, if I rearrange this a bit, do you think you would be comfortable with me using this as a lyric for one of my projects?” And she was really happy about it, and it meant a lot to me as well. It gave added depth to the song. I also know that for the last few years that me and Ole spoke, he always wanted to do music again and to have his work released. But in the end, he had to succumb to what was going on in his mind. I was glad to kind of be able to pull him out of the grave for one time and present his words for anybody that’s interested in the fact that these are the words of a man that’s basically decided to end his own life. I’m not trying to exploit it in any way because I know that this would have made him happy. He was a close friend, you know. So, in a way, I’m honoring his wish as well that, at last, he could contribute something creative. Again, it meant a lot to me. When I was making the song and setting it up, it felt like, yeah, this is work that really means something.

That’s really powerful, and I’m sorry he ended his life. So, we have “Endeavour” on Omniverse Consciousness, and that kind of parallels Black Medium Current’s “The Voyager” and also some words from “Requiem Aeternum.” So, now, we have: “This Voyage is cursed, I hope I’ll be ready, To face the worst…” And before, we had: “Love is a curse, nothing could be worse, The sign of human grief, Rooted in belief.” I say that to myself all the time, by the way. I can’t name them all, but I noticed a lot of other parallels. For example, on “Abyss Perihelion Transit” and “Endless Distance,” there’s some similar imagery with the chains and the harness and all. And I think we even get a nod to Lars-Emil on the latter. You say, “so nothing is,” and his band obviously is If Nothing Is, which you contributed to. So, yeah, there were a lot of places on Omniverse Consciousness where I was reminded of Black Medium Current, A Umbra, and more. Is there anything you would like to say about the fact that, as you mentioned before, Omniverse Consciousness and Black Medium Current are companion pieces in a way?

I think the Omniverse Consciousness album is kind of a companion piece to several ideas. I wanted it to be a more chaotic, intense reflection of Black Medium Current in one sense. But then, in another sense, it’s also a “what if.” What if there was a release between the EP Satanic Art and 666 International?! What could that potentially have sounded like?! And that was really the model, that was really the artistic framing to work with, to start out with anyway. And I did a test run with “Then, to Darkness Return.” It was like starting with nothing, entering the studio, and 8 hours later, it’s done — the music is done, the lyrics are done, it’s recorded, it’s finished, it’s mixed, it’s mastered. I think I wanted to go with that model because that would be the best way for me to latch onto those end-of-the-’90s products, where you had low budgets, and you didn’t really know how to go about things. A lot of what you did was about just experimenting and seeing how things turned out. I tried to simulate that, making everything on the fly and putting myself under pressure and hoping that decision would convert into some real tension in the music.

“Then, to Darkness Return” sounds different than on the Peaceville comp [Dark Side of the Sacred Star, 2022]. You decided to give it a new mix?

The difference is that the drumming was replaced with Camille’s drumming, and there is a new mix and a new master. It’s also nice to set them apart a bit so that the version on the compilation also can have its own life instead of just being part of something else.

I’m interested in the technical aspects of engineering and all. What was it like to record and mix Omniverse Consciousness?

Again, I consciously chose the method that a lot of this had to be on the fly. I was very comfortable working that way. It’s also a lot about accepting what’s coming out without reworking it much or doing a million takes on the guitar, just accepting that whatever you are channeling right now is what it turned out to be. There’s always a time issue because in between making this album, I had to go to festivals and tours and do other types of work. I have a full-time job. I’m also a father. So, many times, one of the biggest challenges when doing art on a pretty underground level is that you have to be really-really passionate about it in order to put the little time you have left to relax or to go abroad on vacation or whatever into just focusing 100% on the art. As for the mixing part, if you accepted A, you have to accept B. And A was like, okay, total acceptance of what you have recorded, don’t rework it, don’t redo it, don’t do anything like that, unless you made a horrible mistake, of course. Then, that process kind of bleeds into the mixing situation as well because you are kind of left with the choices you made. So, there’s only so much you can do in the mixing situation, but I wanted it to be that way. I think a bit of the charm of the old albums from the ’90s is that people really didn’t know what they were doing. They just did it, and it turned out the way it did. I remember when we did the Ved Buens Ende demo, Those Who Caress the Pale, ultimately, I was really surprised, which is strange because we had already rehearsed those songs for one year. Obviously, I had heard them a thousand times, but then when they got dressed up in the studio sound and with all the layers attached and the vocals, I was blown away. I was like: “Fuck, is this what we sound like?!” And I kind of wanted to revisit that sort of experience while doing the Doedsmaghird album, that it’s so fresh when it’s done it’s even new to you. Even if it’s done, it’s finished, it’s like listening to something for the first time.

I do want to mention for the sake of readers that Those Who Caress the Pale is 30 this year. Sorry if I’m being a bit repetitive and silly because we kind of touched upon it last time we spoke, but for Ved Buens Ende, it still seems unclear to me as to whether I should be saying that it was founded in ’93 or ’94. The line is a bit blurred.

I think the initial talks between me and Carl-Michael happened in ’93, but we didn’t even start to actually rehearse until ’94. Maybe it’s just because it was the winter… I’m not sure. Maybe we actually managed to have some rehearsals in ’93 as well, but it was around that time. Things were very undefined in the first stages of Ved Buens Ende, meaning that we also played the Manes songs like “Når solen stivner” and “My Blackhearted Flower” and a few other songs I had. Eventually, a lot of the stuff I made for Manes went into the Ved Buens Ende moniker. That’s why maybe it’s a bit difficult to say exactly when we started, but, yes, we were in deep talks already in ’93 and perhaps also had a couple of rehearsals before ’94, but I’m unsure if I moved to Oslo in ’93 or ’94. It was Easter, I guess. Maybe that was Easter of ’94. My mother drove me to Oslo, and she said: “When are you coming back?!” And I said: “I don’t know.” And I stayed, you know, and I’ve stayed ever since.

You’ve said that Black Medium Current might be part of a trilogy. Do you still think that?

Yeah, but sometimes things change. A Umbra Omega was also meant to be a double album. I have a few leftover songs for A Umbra Omega, but, you know, sometimes the label says: “No, that’s not sensible, Yusaf. It will be too much.” And there were time constraints and all that. So, it ended up being what it was. Right now, in terms of what we are doing on Black Medium Current, where any song can go in any direction, I feel that there’s much more to explore there. I don’t want to close that chapter just yet because we took this set of nine songs and made them go in specific directions, and I think there are still many more places you could take things on the next record, having Black Medium Current as the recognizable base work. So, yeah, the trilogy is still intact in the plans, but that can be abandoned at any point.

You have so many great shows booked. You’re going to Serbia, Chile, Barcelona, Germany, Athens, and London. But when Black Medium Current was released, you were in the United States at Metal Threat with Ved Buens Ende. Fellow Norwegians Aura Noir [with Carl-Michael] and Slagmaur also performed. Do you have anything to share about that experience?

It’s always nice to get out of the regular loop. I love going all places, of course, but some places you have traveled to more than others. When we get the chance to go to South America or North America, which is more seldom, it’s very much appreciated. Last year, we also had a trip to Tasmania, which is, to date, our furthest trip. We traveled all the way from the north to the very south. Obviously, that creates memories, right?! It’s easier to remember those one-off shows. If you’ve been to Paris 20-30 times in some shape or form, it all gets jumbled together in a sense. There’s not really that much of a distinct memory of each show, but it’s more like an amalgamation of all the shows. So, getting to go to Chicago, and Mexico, and Tasmania, and all that stuff, it really sticks out.

This year, you played at Steelfest and Brutal Assault, which are both really cool. We already mentioned Beyond the Gates. I didn’t actually realize until recently that you were in Oulu with Beherit. How was that?

Yeah, our show was very good. I love the Finns. They’re so grounded and hospitable in their own little bit of a shy, introverted way. Finns are very loveable like the rest of us Nordics — Swedes, and Danes, Icelandic people, and Norwegians. I think the Finns are slightly different though. People from Oslo and Stockholm are probably more similar than Finns from Oulu. So, I always really enjoy my time in Finland a lot. And a lot of times, I stayed behind after shows, just stayed behind a few days or a week or whatever before I’d go home. I feel a real connection there. Unfortunately, with the Oulu show, I missed the Beherit show. That was something that I was really looking forward to. The Oath of the Black Blood was one of the first black metal records that I bought that was really over the top black metally in how it looked and how it sounded and how it felt. Those first two records by Beherit are favorites of mine within the genre. So, I was really looking forward to seeing them onstage at last, but I was stuck in their airport. There were some delays with flights that made it so that I, unfortunately, didn’t see them.

Sorry that you didn’t see that. [But you would have been the highlight of the fest anyway.] Edvard [Rødseth], your bandmate in Strid, organizes Imperium Festival. You played at the open-air fest in Halden and also at the “sieges” with various groups. Do you know if the open-air fest is ever going to pick up again?

I don’t know. I don’t want to blame anybody, but I think maybe people don’t realize what a spectacular place that is to have a festival. Edvard did a lot of cool things as well that were quite new. He utilized a lot of rooms in the fortress and their acoustics. I think if that festival would have had the opportunity, it would have grown. It could have become something really special. For anybody that’s blackpacking to Norway, I think they would have gotten a much more coherent black metal experience going to Halden, seeing how the nature looks over there, and then having a festival in a fortress, instead of going to Oslo city. I love Oslo though, so I’m not shitting on it in any way. But, yes, I think that it would be a shame if the festival doesn’t continue.

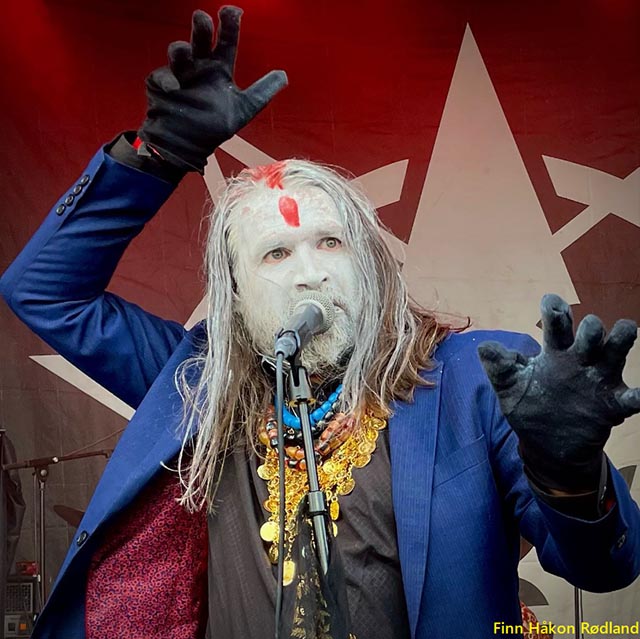

I hope it will continue. On the topic of live performances, I would say that a lot of my favorite black metal photographs are of you. NecrosHorns just photographed you at Brutal Assault. Arash Taheri has captured you. Carl Eek has taken nice photos of you and contributed to the Dold Vorde Ens Navn releases. Finn Håkon Rødland has some amazing shots as well. In addition, Dødheimsgard has had some of the best booklet photos and art in metal. You’ve worked with a lot of great designers like Trine [Paulsen] and Kim [Sølve], but you’ve also created some visual art for your music. What can you tell us about that?

It’s a new thing for me. And, I guess, it’s an app age. So, I’m really an amateur. I don’t even use a computer to do it. I do it all on my phone, basically, the cutting and splicing and filtering. Sometimes, I get very restless in the sense that I’m at home, and I’m not in the mood to pick up the guitar or write some lyrics. And I don’t want to watch TV. It’s been nice to pick up other tools that you can go into and utilize, and then, it results in something. You create something that wasn’t there before you started. Doing visuals is one of those things. I do it with love. I have no desire to make money off of it or anything like that. I just want to do it once in a while when I feel like it.

Speaking of your other band Dold Vorde Ens Navn, you said that you were collecting tragic stories around Oslo and trying to use them for your lyrics. I know that Ved Buens Ende is also working on new material. Strid has been doing so as well. Is there anything you would like to reveal about the progress of any of those upcoming releases?

Yeah, we are deep down and dirty in the Dold Vorde Ens Navn process. That’s going flawlessly at the moment, I think. Haavard maybe has some finishing touches on one or two songs. The rest is done composition-wise. It’s not all recorded. I started laying down the vocal tracks. Of course, I can’t always stay home. I have to go out on the road. So, it will be disjointed, but I hope to be finished with the vocals before Christmas and can add those files into the bank, so to speak. But, yeah, I don’t think it will be that long before Øyvind lays down the drums, and we get all the layers collected, and then it will be a done record. With Ved Buens Ende, it’s much more complicated because it’s been all these years since we did something. For me, it’s very important that it actually makes sense so that it’s not just a new cover with a Ved Buens Ende logo. The biggest inspiration for a new Ved Buens album should be the old Ved Buens Ende album. We don’t need any other inspiration for it. It’s all there. That’s my take on it: A new Ved Buens Ende should reflect heavily on Written in Waters and pick up where we left off, not where we are as musicians in 2025 and turn into something else. Then, the logo on the album cover will make no sense other than just being a logo on a cover. I will say that I made four songs for it, and those are there to be utilized. Hopefully, Carl makes four, and there you go.